Brynne Kennedy speaks Mandarin, French and Portuguese and is well versed in investment banking vernacular. But five years ago, when she flew to California from the UK to raise funds for her tech startup, she had to learn a whole new language.

Venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and San Francisco were using terms and phrases she’d never heard. Kennedy immediately set herself a reading list of biographies of successful techpreneurs and studied up on technical terms.

The result? The graduate of Yale University and London Business School secured $35m in funding for her company, MOVE Guides, a software service provider for global relocation.

“You need to speak the language to play the game,” the 33-year-old says. “Once I did that I was able to successfully build relationships in the Valley, successfully raise money and successfully grow and lead our company… Now I live here so it’s all kind of standard, but five years ago it wasn’t.”

But even if you never set foot in Silicon Valley the language spoken there — known as technobabble, geek speak or Valley lingo — is increasingly inescapable. And that, say language experts, makes it something many of us speak without realising it, and something the rest of us should learn, even if we’re not squarely associated with the tech world.

In much the same way that corporate management terms such as ‘circling back,’ ‘brainstorming’ or ‘blue-sky thinking’ once infiltrated everyday language, as the influence of technology on the economy continues to grow, there will likely be a welter of new terms to add to our vocabulary.

Kennedy was highly motivated to learn the lingo, and set her initial focus on technical terms such as ‘series A funding’ and ‘series B funding’ (first and second rounds of outside financing) and ‘product-market fit’ (extent to which a product matches market demand), rather than more colourful expressions such as ‘sunsetting’ (phasing out or discontinuing a product or service) or ‘eating your own dog food’. (No, that doesn’t mean actually eating dog food; it means that a company tests out its product or service in-house before bringing it to market.)

Light Speed

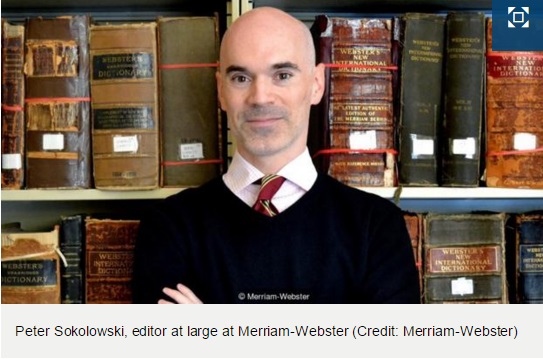

Startup and tech jargon are growing at an exponential rate. Freshly coined terms such as ‘clickbait’, or new definitions for existing words such as ‘unicorn’, are finding a place in everyday conversation. Technology is even one of the three richest sources of new words for Merriam-Webster, says Peter Sokolowski, editor at large for the long-established dictionary of American English.

While it once took decades for a word to move from specialist usage into the mainstream, the process has accelerated to ‘light speed’, partly thanks to social media, he explains. ‘Television’, for instance, was first noted by editors in 1906 and adopted in the dictionary in the 1940s. But ‘humblebrag’ — used to describe a seemingly modest or self-critical statement that is in fact meant to draw attention to one's impressive qualities or achievements — is already included, despite only being picked up by editors in 2011.

Of the 1,000 new words and definitions added to Merriam-Webster.com in February, terms related to tech and to social media range from 'abandonware' and 'backward compatible' to 'NSFW' and 'white hat'.

If you flinch at these, or feel baffled, you’re not alone. “We all object to novelty in language,” says Sokolowski. But as frequency increases, we start using new phrases without the same self-consciousness, he says.

For instance, the word ‘blog’ — a shortened term for ‘weblog’ — was first spotted by editors in 1999 and within five years was in the dictionary. “It may be an ugly word and a word people objected to initially but we needed a name for this thing,” says Sokolowski. “People probably wearing flip flops in Silicon Valley made a two-syllable word into a one-syllable word that they all recognised.”

A sign of status

Silicon Valley’s experimentation culture naturally generates new words to describe innovations in financing, product development or marketing, says Steven Ganz, co-author of Valley Speak – Deciphering the Jargon of Silicon Valley. But it’s also a result of the trend towards personal branding and innovators attempting to corner a market, he says.

“People want to claim intellectual turf for themselves, not that much different than what people try to do in academia by carving out disciplines for themselves. But this is in a business setting.”

Words and terms invented in Silicon Valley are quickly exported. In the IT sector, words become very quickly in fashion in the US and then get passed to the UK, says Rob Steggles, senior marketing director for Europe at telecommunications giant NTT Communications in Paris, France.

And many people are keen to have the freshest tech talk tripping off their tongue. “In the UK and America, by using a term like ‘algorithmic computing’ or ‘agile development’ it’s almost a code for signalling you’re one of the ‘in crowd’ who understands these terms,” says Steggles. “If you can speak like that, then you’re up-to-date with current events — there’s a subtext that goes along with it.”

While tech talk makes sense between insiders, using it in non-technical business conversations might not be as useful, warns Jamie Sunderland, strategy director at Neu, a digital product development studio in Glasgow, UK.

“Every industry has insular jargon and acronyms,” he says. “The challenge is when they become too widespread and then detach from their original meaning, ending up being used to hype conversations and make management feel relevant.”

The key is not to get distracted by fancy words in the way you describe something. “You have to try to drop the ego a little bit and get into the eyes and the shoes of the customer and the user who often doesn’t speak like that,” Sunderland explains.

Tech and startup talk can sometimes be overused by people simply trying to look cool , says Ganz.

More and more, though, Kennedy hears geek speak infiltrating conversations a long way from the workplace.

“My mother knows some tech terms, for example, just by listening to NPR [National Public Radio] or watching the news or whatnot. So many tech companies are talked about so regularly,” she says. “I think that’s reflective of the fact that tech companies are much more prevalent now and a larger share of the economy.”